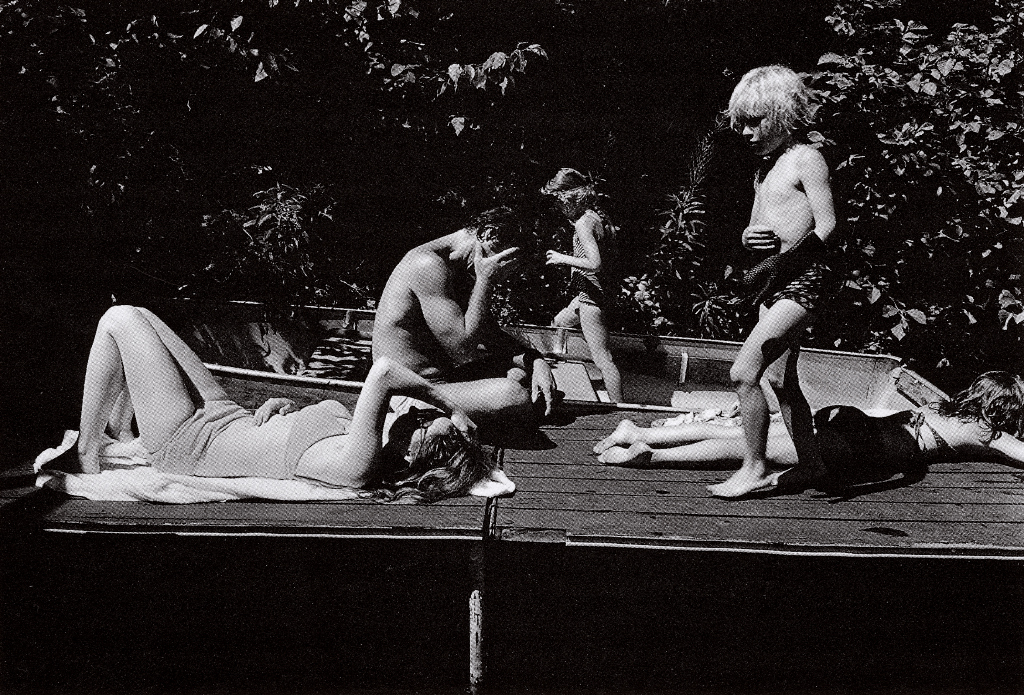

Anna (Jake and Laura), 1978

The Guardian

The doting amateur makes no claim to high art, but it is precisely the same concerns about privacy, artifice, and the potential for unintended provocation that inform reactions to those who work creatively inside the domestic sphere, then make that work public. Since the 70s, artists like Nan Goldin, Dick Blau and Robert Mapplethorpe have used photography to challenge our cultural ambivalence towards images of children. Their project has been to overthrow the 18th-century Romantic idealisation of childhood in art, which fetishised children for what they were not: not sexual, not knowing, not polluted by adult experience, and, in so doing, to challenge the viewers’ interior sense of what childhood ought to look like.

Libby Brooks

Breakfast with Special K, 1980

Living With His Camera

Blau’s talent for finding the perfect picture in the mundane moment is evident from the many photos presented with the text.

Liz Miller, Bookslut

Pictures of Innocence

Children and adults may not enjoy the world they share. What children know about adults is not always pleasant. Dick Blau confronts us with the bleaker possibilities. In his grim Family Scene (1978), the adults seem to have given up, hands over their eyes, slumped and weary. Two children plod on, both moving blindly in the same directions, their rhymed movements pushing against the adults’ static bulk. The seam of the dock, right in the middle of the foreground, acts as a psychological barrier between the opposed forces of adult and child. This is the kind of scene no one would want in their family album, including Blau. His partner Jane Gallop puts her snapshots in the family albums instead. Blau has told me he and his family find it hard to look at some of his work, this photograph in particular. Yet it expresses, in part by the ordinariness of its moment, in part by the extraordinariness of its insight, a side of family life that shapes family identities as surely as happy, smiling Kodak moments.

Anne Higonnet

Routledge, 2000

Pregnant Pictures

Few photographs other than snapshots take on the feelings of grotesqueness that can accompany pregnancy; in snapshots, expressing such feelings can be accomplished with a light touch. Dick Blau also points to the humor of the near-term pregant belly, using clinical measurement as an ironic sign.

Strategic multiplication and indexical pointing within the pose nearly always result in caricatures of already exaggerated female bodies. The pregant body is not represented in family photographs as too powerful, however. Humor mostly serves the function of enabling a subjective representation and, simultaneously, disarming it.

Sandra Matthews, Laura Wexler

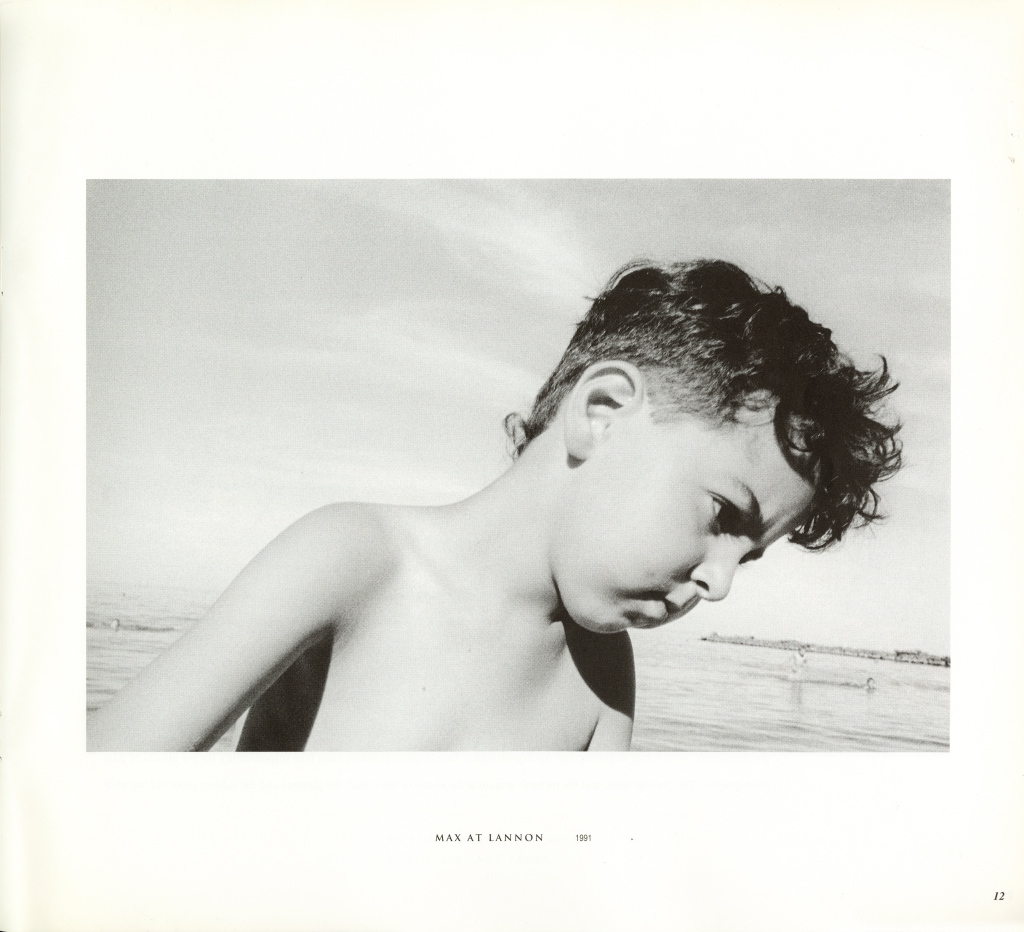

Lannon Quarry, 1992

New Wisconsin Photography

Photographing ourselves has become, perhaps, Americans most universal family ritual. In this country we took over ten billion family pictures last year, comprising roughly two-thirds of all photographic exposures.

Though many pictures are made, it is astonishing how few we end up caring about. We are surprisingly ruthless curators of our own family histories. We edit out all of the “bad” pictures—people with their mouths open, eyes shut, those who Didn’t smile quite right. A lifetime, tens of thousands of pictures, is easily distilled to less than a handful of moments. A grandparent, for example, is usually remembered by one or two official portraits, often of his or her own choosing.

Why are so many snapshots needed to say so little about their subject? Why do we edit out all the pictures that remind us who we really are? The truth is that we take most pictures not for our private use but for public display. Decorum requires we do not burden our guests with our family secrets, our despair, our particular natures.

Artists who photograph their families in their art start by violating this seemingly universal convention. To make interesting pictures, photographers have to forget about making their loved ones look nice. They have to forget about the civility that pervades our presentation of family life. The complexity and ambiguity that usually follows is difficult to manage.

One way, then, for photographers to distinguish themselves from amateurs is by making their loved ones look either unhappy or ugly, or both. As a result, we may be initially suspicious of such serious family photographs. But we are wrong to suspect that profundity may be too easily attained simply at another’s expense.

Tom Bamberger

Ioannis Dramalis with dancing couple, 1994

Bright Balkan Morning

Dick Blau’s amazing photographs give the book a sense of presence, the intimacy of people viewed up close and distant, always lovingly, with respect and with awe. There’s an inviting pulse here, an energy and inwardness that take human shape; rapt bodies register and make palpable an unheard music. Blau’s camera dances with its subjects and makes them real.

Alan Trachtenburg

Giorgos Liondas and Dimitra Lionda in the yard, 1994

Bright Balkan Morning

Dick Blau’s photos are not just a set of pictures, but more or less a living, organic part of the plastic picture of the Romani life and music in Greek Macedonia. It is thanks to these photographs that we can get a better feeling for as unique world that can never be presented by words only. Some of the illustrations are reproductions of photos from private collections of some of the musicians—the guides of the authors in the amazing atmosphere of Iraklia. According to Blau these do not just bear a personal meaning but are also a documentation of the achievements of a society—that of the Roma of Jumaya (Iraklia). The past of the mahala—family pictures, weddings, working days in the field, vacations and mostly of playing and dancing—is included in the picture of Romani Iraklia, seen through the photographic eye of Dick Blau. As a true anthropologist, Dick Blau is not interested only in making a pictorial documentation of portraits of the instrument and the player in action of performance. In his photos we can feel the spirit of Iraklia, captured in the images of the marketplace, the yards and houses and musicians, the fields and road.

Romani Studies

Yeri with camera, 2006

Skyros Carnival

Carnival as a ritual event, as a rite de passage, and as a source for musical creativity has been the topic of a wide range of publications inside and outside of ethno musicology—but none has ever reached the surprising experimental character of the multimedia publication, Skyros Carnival. It is highly exciting to see the complementary interplay between the four dimensions of sound, text, photography, and video in this publication. The photography by Dick Blau takes a highlighted role in this interplay, as it is employed not as a mere illustration, but as an aesthetic foundation for the issues dealt with in the text…a groundbreaking example for a new way of writing sensual ethnography in the twenty-first century.

Eckehard Pistrick, 2013 Yearbook for Traditional Music

Polish hop, 2013

Polka Heartland

Polka—the style of dance music that originated in central Europe—has a best friend in Wisconsin, which adopted it as the official state dance. Throw in some mugs of beer, squeeze boxes, and the ‘Beer Barrel Polka,’ and it’s all eye-rolling kitsch. Filmmaker/photographer Dick Blau went beyond the stereotypes to nab the joie de vivre in ‘Polka Heartland,’ an exhibit of 30 incandescent photos that ran in early 2015 at the Museum of Wisconsin Art.

Ann Christenson, Milwaukee Magazine

IPA festival, 1988

Polka Happiness

Polka Happiness is an inspiring account, with strikingly eloquent photographs. it is based on material collected over twenty years of visiting dances, fan club meetings, national and regional conventions, interviewing musicians, promoters, disc jockeys, fans, and generally gathering information on’ Polonias’, the Polish areas of big cities. This is research con amore.

The book’s appeal extends beyond the academic; polka people will also read this with pleasure. It is printed in the Visual Studies Series, and with its brilliant photographs, it could almost stand as an art photography book.

Popular Music

IPA festival, 1988

Polka Happiness

My conscious goal as a photographer, overriding concerns of image clarity and density, was always to try to capture the intimacy and spontaneity of everyday working-class sociability, and I was deeply influence by the “snapshot aesthetic”of my subjects’ own approach to photography, and in particular by the work of documentary photographer Dick Blau.

Aaron Rogers