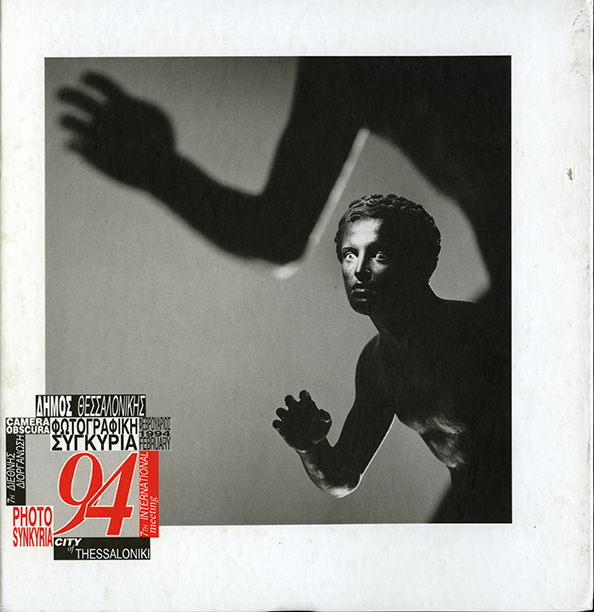

New Wisconsin Photography

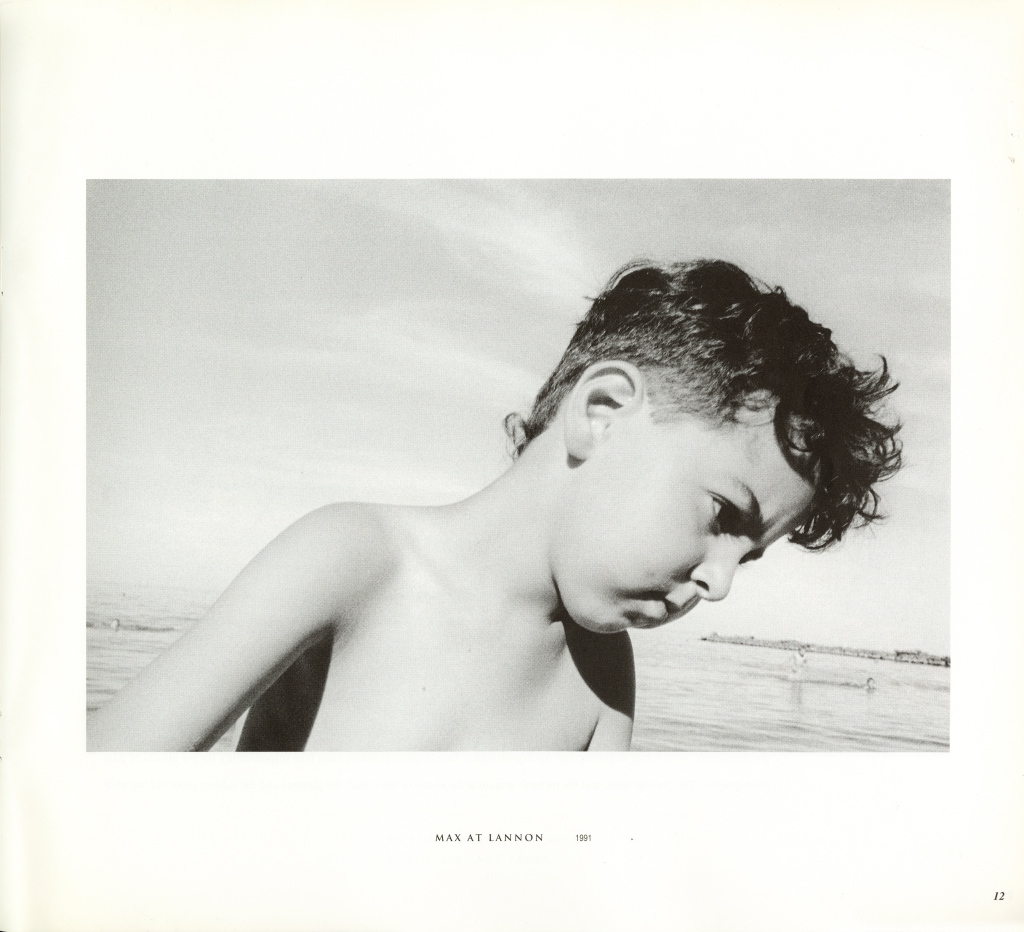

Photographing ourselves has become, perhaps, Americans most universal family ritual. In this country we took over ten billion family pictures last year, comprising roughly two-thirds of all photographic exposures.

Though many pictures are made, it is astonishing how few we end up caring about. We are surprisingly ruthless curators of our own family histories. We edit out all of the “bad” pictures—people with their mouths open, eyes shut, those who Didn’t smile quite right. A lifetime, tens of thousands of pictures, is easily distilled to less than a handful of moments. A grandparent, for example, is usually remembered by one or two official portraits, often of his or her own choosing.

Why are so many snapshots needed to say so little about their subject? Why do we edit out all the pictures that remind us who we really are? The truth is that we take most pictures not for our private use but for public display. Decorum requires we do not burden our guests with our family secrets, our despair, our particular natures.

Artists who photograph their families in their art start by violating this seemingly universal convention. To make interesting pictures, photographers have to forget about making their loved ones look nice. They have to forget about the civility that pervades our presentation of family life. The complexity and ambiguity that usually follows is difficult to manage.

One way, then, for photographers to distinguish themselves from amateurs is by making their loved ones look either unhappy or ugly, or both. As a result, we may be initially suspicious of such serious family photographs. But we are wrong to suspect that profundity may be too easily attained simply at another’s expense.