In rapport with the layered texts by the Keils — Dick Blau’s amazing photographs give the book a sense of presence, the intimacy of people viewed up close and distant, always lovingly, with respect and with awe. There’s an inviting pulse here, an energy and inwardness that take human shape; rapt bodies register and make palpable an unheard music. Blau’s camera dances with its subjects and makes them real.

Alan Trachtenberg, author of Reading American Photographs

AFTERWORD

DICK BLAU

Mid-July and mid-afternoon 1993 in Jumaya, at the northernmost edge of Greece about thirty kilometers from Bulgaria. Here I was, with a month’s worth of the language, an expedition-size camera bag, a suitcase that kept tipping over, and no hat. Giorgos Liondas sized me up, shook my hand, and then started walking his bicycle home. He pushed forward without looking back. We left the center of town and entered the mahala. Tiny white houses lined each side of the empty street. I realized it was siesta and wondered just how much I had annoyed my companion by dragging him out of his bed and into the heat.

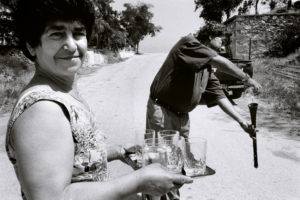

Demetra Liondas was at the gate when we arrived. I shook her smooth strong hand and felt vaguely self-conscious standing there wrinkled in my shorts and sandals, she in a modest house dress and he in long pants and an immaculate white shirt. . She said something nice and went to make coffee. Then Liondas took over again. I would stay in an extra apartment, one of two he had built for their sons when they come back to town. I followed him in , past a small washing machine, sink, and stove, to the dining area. In Greek and gestures, he made it clear that I was to sleep on the couch — not in the bed around the corner. Once I got unpacked, we would have coffee. Then he left.

Opening my bag, I found the bottle of Johnny Walker Black I’d bought on the plane. After I’d washed my face and tucked in my shirt, I returned to the patio where Liondas was waiting for me at a small white plastic table set with two tiny cups of coffee. I stood there for a second, then handed him the bottle. He made no move to offer me a chair. I waited a little more and then sat down. A century passed. “I don’t drink,” he finally told me, and put the bottle aside.

Again we sat in heavy silence. I sipped my coffee and tried to remember the word for children. “I have a boy who is eight and a girl who is twenty three,” I managed. “The boy is Max; the girl is Anna.” Silence. I wondered if I should leave. The thick air stirred. I glanced up into the sky and saw that a large dark cloud had somehow appeared over the roof of the house. Again silence. I tried once more. His children: where did they work? I asked. “Yermania,” he answered. Germany? I asked. “Yermania,” he repeated. “Do you speak German?” I asked. “Ja wohl!” he said, and smiled. There was a clap of thunder and it began to rain.

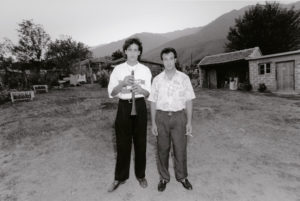

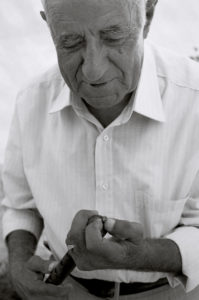

The storm was violent but brief. Steam exploded from the pavement and then it hailed. We were soon enveloped in a cool soothing mist. When the rain had passed, the heat and the silence returned. I wondered if this was going to work. I was trying to imagine just where I would go when he suddenly told me to get my camera. I got it out and came back to the patio, took a few pictures of the compound, a couple of the clouds, and then followed Giorgos around the house as he told me what to shoot. He posed in front of the new marble trim on one of the apartments, with Demetra in their living room, and finally with his dauli on the patio.

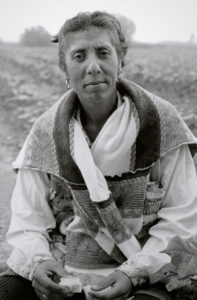

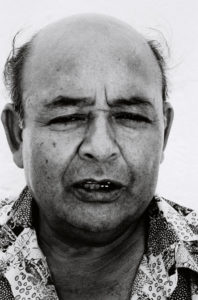

Siesta was now over and people were coming out, so we took a walk to see the neighborhood. We’d pass a house, he’d stop and point out someone to me; I’d approach, muster up my Greek, and ask if I could take a picture. They’d answer by the slightest nod of a head or flick of the eyes. I’d make the picture, but without much confidence. I felt quite off.

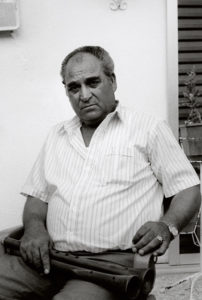

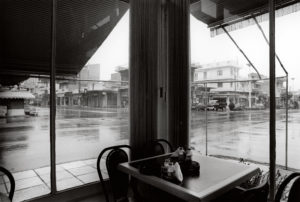

We walked across the shabby platea that defines the center of the mahala. It felt oddly empty, then plunged on until we came to the Dhramalis cafe. He and his two sons were well-known musicians, his coffee shop a local hangout for neighborhood youth. Dhramalis was there, but he hid behind his cigarette. In hindsight, I realized that both he and Liondas had probably just been shy., but at the time I was just glad we didn’t stay very long.

We walked back home, arriving to find a number of musicians waiting for us in the yard. Some had brought instruments along. I posed them against a white wall in open shade. When I had photographed everyone and there was no one left in the yard, Giorgos went back into the house. I followed him into his living room where he took off his shoes, lay down on the couch, lit a cigarette, and fell into a moody silence. Watching him smolder there reminded me of why I had been drawn to photography in the first place. Whatever my interest in ethnography, I am at heart a student of human expression, a portraitist of the feelings. Looking at Liondas on the couch, the other pictures I’d been shooting seemed merely dutiful. I wanted to make this picture, but wasn’t quite sure that I should. So far Liondas had insisted on calling all the shots, but now he said nothing at all. I wondered if he would take offense. I decided I’d do it anyway. He didn’t complain. It was the best thing I did all day.

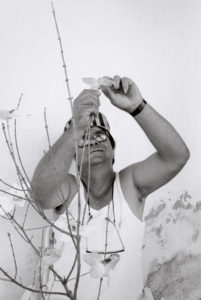

I spent the next four weeks making pictures in the mahala. (I came back the following winter for five days; then I spent another 10 there in summer l996, this time with Angie and Charlie.) I began by photographing around the house and visiting with the neighbors. Sometimes I would go on an errand with Giorgos. When I got a little more comfortable, I’d set off to explore the neighborhood by myself . At first I simply walked the streets; then I tried the alleys. I shot a lot of film in those first days. I was eager to get going, wanted to find my rhythm, wanted people to see what I was doing so I wouldn’t have to explain too much. As I got more familiar with the mahala, I began to stop at places where people were likely to be working , introduce myself, and ask if I could hang around. I’d sit with them in their yards while they made brooms, worked on zurna reeds, or made handicrafts to sell in the Friday market. I was struck by the quality of concentration they brought to every task, and I admired the graceful way they handled their tools. I tried to make my pictures the same way they made their mats. I saw it as a way of talking with them.

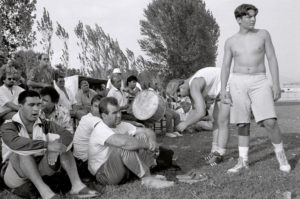

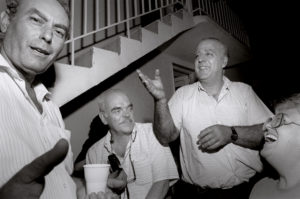

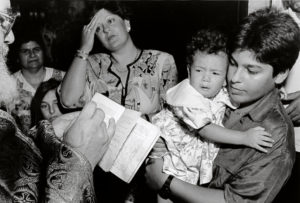

On weekends I’d go out with the trios — four of them in particular — as they worked their way through the summer season. We’d take the one car, the neighborhood taxi, or the bus and travel to neighboring towns and villages. Once we traveled fifty kilometers to a saint’s day, but most of the jobs were within a half hour of Jumaya. When we got to wherever we were going, the spokesman for the group would introduce me and then I’d talk my way into the event.

We played weddings, baptisms, saint’s days and a wrestling match. When I wasn’t shooting, I’d do what their friends did when they came along on a gig: I’d pick up the tip money that dancers would throw on the ground and stuff it into the players’ pockets.

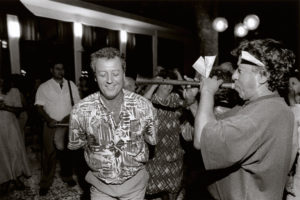

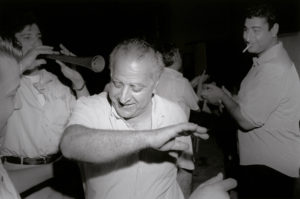

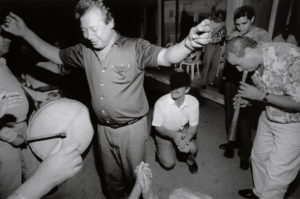

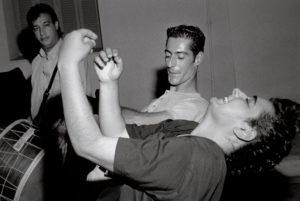

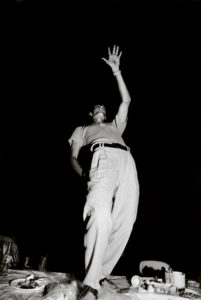

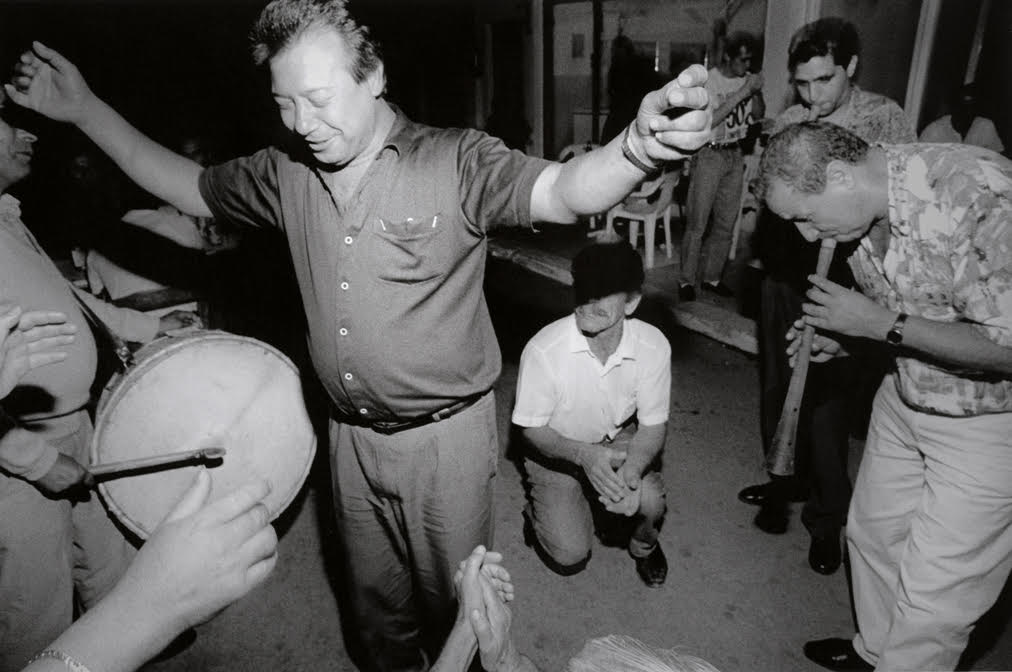

Most events seemed to begin almost perfunctorily, with different sets of table songs, a few traditional dances, and then, if it was a wedding, a procession from house to house to church and back. Up close, the music was overwhelming. Once people got into its field, they became energized and seemed to float as they danced. The sound could penetrate. Pitched high and nasal like an oboe, the zurna’s insistent whine reminded me of an immense swarm of insects somehow compressed to a density that could get into the nervous system and set a person vibrating, push her into motion, invest and inspire him with powers beyond the ordinary.

The dauli, played with both mallet and stick, provided drama of another sort. Negotiating an exquisite line between anticipation and release, the drummer would lead the dancers through an ineffable narrative, suspending them in his silences and then propelling them forward a step or two towards a conclusion that never seemed to really come. The performance built toward the condition called kefi, where extremes of joy and pain mix in complicated proportion. In kefi the moment is transfigured and the gesture profound; in kefi the normal becomes extraordinary and ordinary people are capable of the most astounding feats; in kefi the individual retains his character and yet also becomes part of some larger form of being, becomes the life of the party. Spinning slowly among the dancers with my camera, I tried to join the party too. When everything worked, I’d find the precise alignment and my own form of kefi, picturing these transient miracles of human expression.

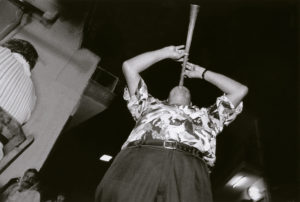

Aside from providing the mind-blowing sounds that drove these parties, the musicians themselves were not particularly dramatic. Every once in a while, the lead player would swing his zurna to the sky and really let loose, but they did not seem themselves to be transported by what they did. No matter what was happening around them, the musicians remained serious, discreet, and somewhat distant from their clients. Although there was a certain air of melancholy to their affect, they never imposed that mood on the party. Above all, they were professional in bearing. One night, when a player had drunk too much and lost the dancers, his partners complained bitterly on the way home. It was four a.m. We had stopped in the middle of the road. Everyone was very angry and their voices were very loud. I kept my head down and my camera in the bag.

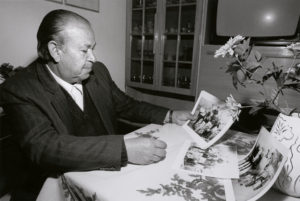

When I wasn’t making my own pictures, I tried to look at theirs, to see what images they had cared to keep. I asked around for photo albums and found a number of them. In addition to individual portraits, army pictures, and family events, a good number showed people at work. One of my particular favorites has a family standing triumphantly on a house they are about to finish. In another, we see the thrill of a new sewing machine. Taken together, I think the meaning of these photos is more than simply personal: these pictures represent the aspiration and accomplishment of an entire community.

When I first imagined photographing “Gypsies” in faraway Jumaya, I had no idea I would find them so close to the mainstream. Once I got over the shock of discovering that the Jumalidhes lived in houses and worried about cholesterol, I realized the actual project before me was very different than the one I had anticipated. In some ways it was even more exciting. Although a possible encounter with the exotic has its appeal, in the long run an engagement with the normal can produce a richer yield.

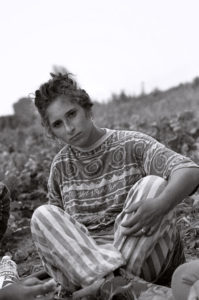

Nonetheless, I still wondered where the other Roma were. As I spent more time in Jumaya, I eventually discovered that a more “classical” Romani group did indeed live there too. Every once in a while, I’d see a few kids who looked like street urchins in the market . When I asked my hosts about them, they would begin to complain: about how the “road gypsies” stole, stole even from them, how they gave everyone a bad name. One person I asked went out of his way to give me a lecture. “When you write your book, Dik, you must say that we come from India and they come from Turkey.” “But Antonio,” I argued, “don’t you speak the same language?” “No, Dik,” he said: We come from India. They come from Turkey.” I let the matter drop.

It was close to the end of my last visit when I stumbled onto the other place where Roma lived. One morning after having been refused a ride, Angie and I were trying to get out to an agricultural work site by ourselves. Walking along an irrigation ditch on the outskirts of town, we came upon their encampment. Looking down from the berm, we saw a shattered house, a couple of broken down cars, some goats, and an old woman sitting beneath a rudimentary shelter roofed in tattered plastic. Jumaya’s municipal services were generally quite good, but in this case they seemed to go no further than the city side of the ditch: there were piles of garbage everywhere. An angry dog began to bark, then others followed. We minded our own business and tried to get out of range. All of a sudden, a man came out of the house. Hey,” he called to us in English. “How you doing?” We were tempted to stop but didn’t: it had been hard enough to get out to the fields and we were leaving the next day. We just waved back and kept on going, deferring this part of the story to another time.